Since the 1970’s, undergraduate enrollment in the humanities–English, history, fine arts, and philosophy to name a few–has steadily dwindled to half of what it used to be. These majors, when scrutinized under society’s paycheck-obsessed lens, don’t hold up well. Forbes list of the worst college majors, according to income and unemployment rates, ranks these dreaded “soft” majors among the top ten.

These statistics–paired with the impending burden of college loans, bills, and a bad job market–are enough to leave any humanities-inclined student worried. So worried, in fact, that many are scurrying to alleviate stress by finding a different major with a secure job and large paycheck waiting with their college diploma.

But, how much are students willing to sacrifice to secure this safe future?

According to a recent article written by Scott Saul in the New York Times, students who dedicate themselves to popular STEM majors–science, technology, engineering, and math–may sacrifice learning universally desired skills that all employers seek when considering a job applicant, skills that are central in any humanities education.

In humanities classes, students have the opportunity to hone critical thinking skills, question ethics, connect to others with newfound empathy, and expand their perception of different cultures, people, and ideas. This, along with much more, demonstrates that the value of a humanities education far outweighs any monetary standards.

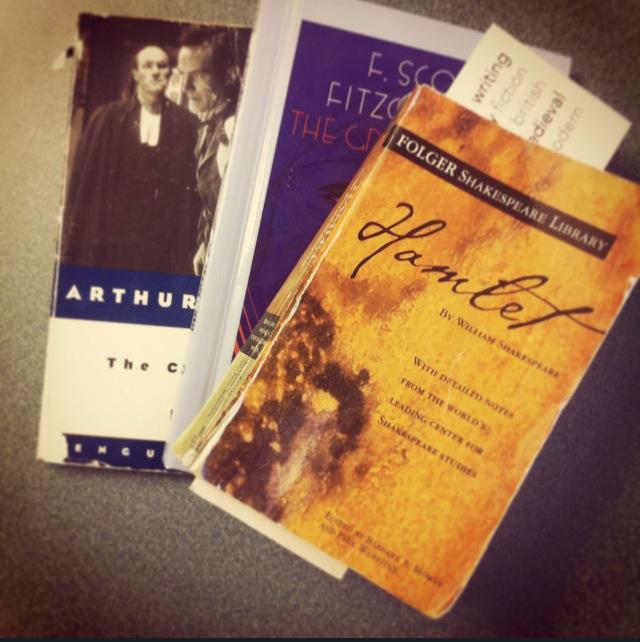

Take English majors, for example. These students immerse themselves in literature, open portals to new perspectives, and delve into questions concerning anything from love and ethics to politics and religion. This process inevitably leads to the broadening of one’s perception of the world, as well as practical skills like critical reading and writing ability.

Ludlow High School English teacher, Christopher Rea, sits leaning back in his chair, his electric guitar socks peeking out from the cuffs of his pants. A Hemingway quote is scrawled on the chalkboard above his head, a stack of books sit upon his desk, and a Picasso painting and Shakespeare portrait are pinned to the opposite wall. As an English enthusiast himself, he highlights that, “If you’re interested in the humanities you’re interested in human nature, in life itself. You’re interested in exploring the nuances of the human mind and language, which I think are detached from a practical, road-map to a specific career.”

Instead of putting all the focus on the practicality of one’s passion, Rea claims that, “To me, genuine curiosity should be at the heart of education.”

When curiosity is suppressed the education system and ultimately the well-being of the country suffers. Without driven, passionate students no advancements are made in any field. If motivated students are driven away from their passion instead of toward it, they may not only end up unfulfilled, but others will miss the impact that they were bound to make.

Rea continues, stating that, “I feel like curiosity is going to take a hit. People end up in the humanities because they’re driven by a curiosity about ideas and art and values. I get concerned when anybody tells me that their future is only concerned with a certain quality of life or degree of wealth, because I think that people sometimes ignore the wealth that comes from enjoying learning.”

In addition to enjoyment, Rea believes students will miss out on the realizations that inevitably present themselves whenever studying literature. Books provide humans with a way to connect their own experiences to those of others who have lived before. He says that this provides people with a way to consider ideas of the past, compare them to the present day, and apply this new perception to their lives.

Brian Bylicki, head of the Ludlow High School History Department, sits behind his desk with political bumper stickers plastered on his wall and a magnet sticking to his chalkboard featuring George W. Bush asking, “Rarely is the question asked: Is our children learning?”

In a matter-of-fact voice he states, “The humanities help you write, read, and think.” With a small smile he then casually adds in that, “This can become very controversial.”

According to him, controversy arises when history classes delve into deeper questions about our past. He believes that government intentionally encourages an emphasis on a STEM-focused education, opposed to the humanities, because it keeps students from questioning events and ideas that may end in disagreements, protests and ultimately, change. For example, deep knowledge of history spurs questions over the ethical reasoning behind events like the dropping the atomic bombs on Japan or taking over land from the Native Americans.

Bylicki claims that standardized testing is one of the biggest factors working to divert attention away from the humanities. He asserts that standardized testing fosters an emphasis on rote memorization while abandoning critical thinking and reasoning skills. That, along with the education system adding more weight to math and science, is causing students to become less interested in subjects like English and history.

Straying from subjects like this, according to Bylicki, is detrimental to the individual as well as the country. In fact, he claims, “The humanities make us and separate us from a technological society that doesn’t think about the past or try to project the future. Without the concept of the Renaissance or the American Revolution, we lose track of human history.”

Without a firm understanding of the past, decisions concerning the future can be made hastily and without consideration for prior mistakes. Additionally, the ability to understand the world from a global standpoint, not merely one’s own perspective, is strengthened with knowledge of past experiences–which can be found in anything from a government treatise to the lines of a poem.

Despite the vast array of students at Ludlow High School, it is difficult to find people whose love for the humanities has manifested into the form of a college major.

Senior Mary Silva, who plans to attend the University of Massachusetts, Lowell next year as a history major, is an exception.

“I’ve always loved learning about history,” she claims. “I want to study it in college and continue with it after because it’s my passion.”

Despite urges from others, she does not feel discouraged by her choice. Although her future after college still remains undetermined she says that despite the uncertainty surrounding studying the humanities, “If you enjoy doing it, then you shouldn’t let anything stop you.”

Rea reiterates this same point, stating that the key is to find a passion, pursue it, and then find a way to get paid for it. He offers his advice, stating, “Think about your daily life. Whatever you’re passionate about, pursue it. To the humanities folks specifically, don’t settle for a different profession because of a paycheck. Do what makes you happy. Do what you’re interested in doing. It’s a wealthier life; it’s a fuller life. We need you. We need those people.”

If you pay any attention to the experts, you’ll find that humanities majors may not end up completely ridden with debt and eating a solely Ramen Noodle diet after college anyways. Not only would you spend four years pouring over what you love, but according to this article in the Business Insider, the knowledge you’ve acquired would be a valuable asset in today’s job market. Humanities graduates who can think and write effectively are labeled an “endangered species” that are in high demand.

So, for those who secretly love solving calculus problems, could enjoy the comfort of an accountant cubicle, or cannot wait to take over Wall Street: you should follow your passion too. You will be able to impress everyone with your predicted starting salary, and more importantly, study what you love in and after college.

But, for students whose passion resides in literature, in art, in human history: you should pursue what you actually care about. Anyways, who needs lots of money for fancy vacations when you have a job you don’t constantly want to escape from?